LITTLE ORPHANT ANNIE *Special Restoration Review* by Glenn Andreiev and David Rosler

- Jul 16, 2019

- 7 min read

*All Little Orphant Annie restoration images are original to FIR*

Directed by Colin Campbell

Written by James Whitcomb Riley, Gilson Willets

Cast: Colleen Moore, Tom Santschi, Harry Lonsdale

1918 Selig Polyscope.

Film Historian Glenn Andreiev

There is something delightfully magical about silent film fantasy that can't be duplicated in sound films. Think of the museum-worthy images from silent classics like THIEF OF BAGDAD, METROPOLIS, or A TRIP TO THE MOON. The long obscured 1918 film LITTLE ORPHANT ANNIE ranks with these silent fantasy masterworks.

It's a film rich with "Gobble-uns", witches on flying broomsticks, and a gathering of dreamworlds. It was produced by the Selig Polyscope Company and starred the up and coming Colleen Moore, who would later become world beloved as a silent screen flapper. The film would utilize delightful fantasy costumes and visual effects. (Part Two of this review, written by my Special Effects wizard colleague, David Rosler, talks about ANNIE's effects in great detail)

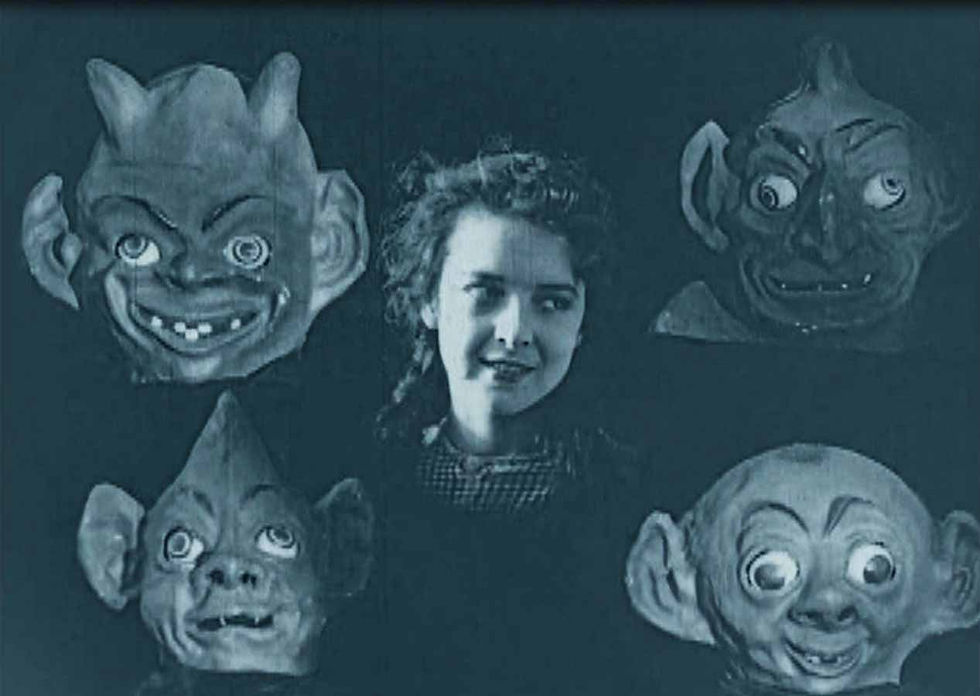

LITTLE ORPHANT ANNIE is based on an 1885 poem by Indiana's own poet/humorist James Whitcomb Riley. We follow Young Annie (Colleen Moore) as she is adopted by her mean-spirited Uncle Tomps. The way the cruddy looking and spirited Tomps tosses aside Annie's cat, you want to tear into the screen and clobber him. The cat, and Annie, survive his abuses unscathed. Annie winds up with the Goode family, and becomes a beloved big sister, and protector of the Goode children. To keep the kids in line, Annie tells them stories about what happens when you disobey your parents, or refuse to say your prayers. "The Gobble-uns'll gift ye- ef you don't watch out!" And the goblins are depicted with wild visual flair. It's why we watch movies - to be treated to great visuals that tell a compelling story.

Colleen Moore, as Annie, is bursting with energy here. Her Annie is not just a feisty girl with tomboy seasoning. She is a budding young woman. She develops a puppy-love relationship with Dave, a young man from town. The viewer is especially drawn when Dave goes off to fight in World War 1. The film has a special framing device. It begins and ends with Author James Whitcomb Riley telling the story to attentive children sitting around him on a front yard. He already had legendary status while he was alive, so his appearance here is memorable.

The film itself has a rocky history. Selig was going out of business as ANNIE was in production, and the film was released by Pioneer Film Corporation. The film was re-released with sub standard prints in 1926, to capitalize on Colleen Moore's flapper stardom. Over the decades, ANNIE was shown only in muddy prints that denied viewers the original visual magic. Film historian and preservationist Eric Grayson, who helped preserve the early film serial, KING OF THE CONGO, gathered the surviving 16mm and 35mm elements of ANNIE, mostly from The Library of Congress, and embarked on a restoration of the film. The results, as presented in a great DVD, Blu-Ray combo pack makes for fantastic viewing. Grayson's work also shines in an actual 35mm print of LITTLE ORPHANT ANNIE that is now available. And in one of the extras, he tells us how this magical film went from scraps on the shelf to a new life.

Special Effects Review by David Rosler

Through all, one thing must always be remembered when it comes to silent movie special effects, especially early ones, and that's that the very primitive nature of the silent motion picture gives, to day's audiences, a sense of being a documentary film, and subconsciously, that helps sell the effects to the audiences. So the silent films had all the advantage never to happen again: they looked real to unsophisticated audiences at the time the films were released because those films were technologically advanced for the era and they look realistic to today's sophisticated audiences because they are within the aesthetic of a film so old that if not done stylistically, the special effects give the impression of being something genuine. Remember, also, that all camera tricks at that time were exactly that - camera tricks. All the photographic effects were done in the camera; there were no optical labs and certainly no CGI. Whatever you got out of the camera after superimposing in camera, etc, was the last word on a shot unless it was re-shot. There was no fixing it in post. Your on-location or in-studio camera negative was your special effects shot.

The thing about the effects in Little Orphant Annie is that they take you by surprise with remarkable skill, but are not, as some have claimed, "impossible to imagine how they did it." There is a scene of elves gamboling about a kitchen table amidst the wooden bowls. The trick was simple: the elves were far behind the blackened window set (justified as an elderly man opens the window "doors" before the shot) and they stood upon a platform the same height as the kitchen table. Simple perspective photography apparent by the fact that the foreground figures are slightly out of focus. What throws the viewer is the cutaway high angle close-up looking down of a few elf actors jumping around a huge well-made bowl prop and then cutting back to the wide perspective photography shot. It's extremely simple but in this instance very effective.

What struck me in particular is how clean the dissolves and split screens are. Generally, when things of that era were superimposed, or a split screen was attempted in that time, the two images "weave" vertically in relation to each other, giving the trick away, because of the mechanically sloppy image registration from exposure to exposure.

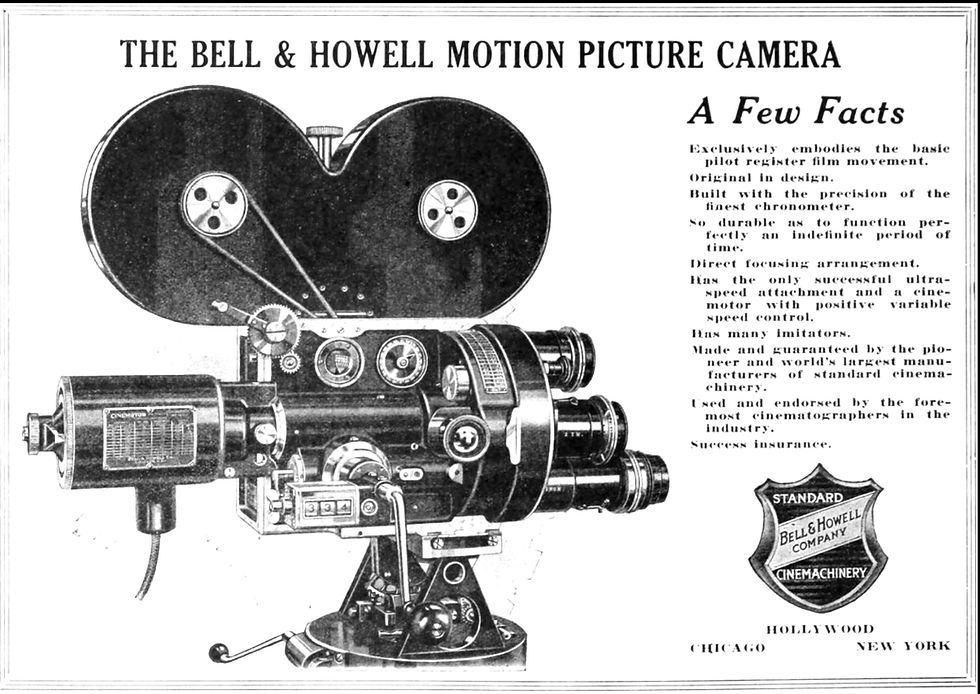

The answer appears to be - I say appears because this is my own conjecture, there is essentially no direct information about Orphant at all save for the studio, the stars and a few release notes - that the producers of Little Orphant Annie, made in 1918, had almost certainly had to have invested in the Bell & Howell 2709, first invented in 1912, but a camera that was very slow to gain traction in the industry, as cinematographers were loath to give up their Pathe cameras so widely accepted up to that point in time. The reason is that the 2709 was the first camera to have what is called 'pin registration". That means as each frame of film was pulled down, it was locked into registration before the shutter opened and exposed the frame. That's pretty fancy-dancy camera-making for a time when people were still cranking cameras by hand. The point is that at that time, the 2709 would have been the only camera in the world capable of weave-less dissolves and split screens. So one must have been on-hand at Selig studios for Orphant.

It is the pin registration that is undoubtedly in great part the key to the effects realism in Little Orphant Annie. When elves and goblins fade into the scene, the effect is occasionally disquieting because these are some pretty weird-looking fellahs - not in themselves all that realistic, but with a unique style and details such as eyes that roll and twitch out of sync with each other; they're all just a tad too disturbing and the perfect fade-in appearance and similar in-camera optics makes them seem believable. Likewise, in a flawless split screen shot when Annie sees herself on the other side of the screen, with the exception of a barely noticeable partial transparency in the left lower corner of the right side of the split, the effect is as flawless as anything digital done today, and while distracted by the action in the upper part of the screen, almost makes you think the actress had a twin.

There were many archaic factors in 1918 that obviously would would have needed to be handled with perfection in unison to achieve that degree of success in such shots, and that makes such moments all the more amazing: hand cranking at exactly the same rate so one side of the scene does not wind up with a slightly different exposure which would give the trick away. Having a rock-steady tripod and I feel certain they were using something more solid than that to kill the slightest vibration which probably would have had to be custom-built. Ensuring the lighting didn't change and this latter is not something to assume because back in that time electricity was still new and voltage fluctuations were common. To add to the confusion and admiration, studios were still employing slanted glass ceilings for sunlight and at the time of Little Orphant Annie's production, the common practice was to have a glass wall and slanted ceiling covered with scrim to soften the light/shadows, along with electric Cooper-Hewitt lights to add to the overall illumination of interior studio shots. Naturally, if a cloud crossed over the sun, or the sun came out from behind one, this too, that would have played total havoc with the exposures for truly realistic in-camera tricks at that time. I cannot help but assume that some shots needed to be done at least twice because the work in Orphant is for all intents and purposes uniformly excellent in terms of maintaining perfect lighting continuity. In the split screen described and shown above, they would have had to also been prepared to work fast and in the right order because the sun would be moving over time, resulting in a change of exposure from one side of the frame to the other. In this case the exposure on the right with all the time-consuming staging, fancy dress, makeup and the like, would need to be shot first and everyone cleared out fast, the actress out of the fancy dress, throw on her nightgown and her makeup changed for the left side of the shot which required essentially no staging let alone time-consuming staging.

It's obvious that genuine painstaking concern was given to these potentially disastrous pitfalls. So much so that the result, an astounding 100 years later, has left many film historians and special effects experts baffled and scratching their heads, not just because the effects are good, but because they are THAT good.

Recapping, my analysis is that Annie's effects, though basic in principle technique even for the day, are mostly entirely successful - and remarkably so for primitive 1918 - because of admirable considerate and delicate handling in the execution of the technical artistry on virtually every point mentioned and the almost-certain application of the Bell & Howell 2709 which was plainly on-the-scene during the production of Little Orphant Annie. The special effects concepts were not cutting-edge ground-breaking even then, but they are generally amazingly well-executed with the best camera of its time for such a purpose.

Comments